🇬🇧 – 🇮🇹

In 1589 the astronomer Philip Apianus died. By order of Duke Albert V he was the author of the famous map of Bavaria and of a globe, published in 1576, with a diameter of 1.18 metres, one of the best of the time. His father Peter Von Bienewitz Apianus observed five comets and was the first to notice that their tail is always in the opposite direction to the Sun. The comet of 1531 he observed is famously Halley’s and his observations allowed Edmund Halley to identify it with the comets of 1607 and 1682.

Nel 1589 muore l’astronomo Filippo Apianus che per ordine del duca Alberto V fu autore della famosa carta della Baviera e di un globo, edito nel 1576, avente un diametro di 1.18 metri, uno dei migliori del tempo. Suo padre Peter Von Bienewitz Apianus osservò cinque comete e fu il primo a notare che la loro coda è sempre in direzione opposta al Sole. La cometa del 1531 da lui osservata è notoriamente quella di Halley e le sue osservazioni permisero ad Edmund Halley di identificarla con le comete del 1607 e del 1682.

In 1793 the French astronomer Jean-Sylvain Bailly (1736-1793) died. Bailly’s first astronomical research was linked to the calculation of the orbit of Halley’s comet, based on observations made throughout Europe in 1759, the year in which the comet reappeared. In fact Halley had announced that the comet of 1682 was in fact the same one that had appeared in 1531 and 1607 and had predicted its return between the end of 1758 and the beginning of 1759. Bailly’s master, Clairault, in a document read to the Académie des Sciences on November 14, 1758, predicted through mathematical analysis with integral calculus (discovered by Isaac Newton) that the comet would be at perihelion on April 13, 1759. This calculation was based on the disturbing influences of Saturn and Jupiter and was intended to explain variations in the comet’s period. The comet initially appeared in the sky in late December 1758 and reached its perihelion on March 13, 1759, just 22 days before Clairaut’s prediction. Thus the studies carried out by astronomers in those years established that comets were celestial bodies distinct from sublunary meteors; not only that, the observations definitively demonstrated that many of them had, as orbits, closed curves, rather than parabolas or mere straight lines; in other words, these bodies had forever ceased to be responsible for superstitions.

Nel 1793 muore l’astronomo francese Jean-Sylvain Bailly (1736-1793). La prima ricerca astronomica di Bailly fu legata al calcolo dell’orbita della cometa di Halley, basato sulle osservazioni fatte in tutta Europa nel 1759, anno in cui la cometa era riapparsa. In effetti Halley aveva annunciato che la cometa del 1682 era in realtà la stessa che era apparsa nel 1531 e nel 1607 e aveva predetto il suo ritorno tra la fine del 1758 e l’inizio del 1759. Il maestro di Bailly, Clairault, in un documento letto all’Académie des Sciences il 14 novembre 1758, predisse attraverso l’analisi matematica con il calcolo integrale (scoperto da Isaac Newton) che la cometa sarebbe stata al perielio il 13 aprile 1759. Questo calcolo era basato sulle influenze perturbanti di Saturno e Giove e aveva lo scopo di spiegare le variazioni nel periodo della cometa. La cometa apparve inizialmente nel cielo verso la fine di dicembre 1758 e raggiunse il suo perielio il 13 marzo 1759, solo 22 giorni prima della predizione di Clairaut. Così gli studi portati avanti dagli astronomi in quegli anni stabilirono che le comete erano corpi celesti distinti dalle meteore sublunari; non solo, le osservazioni dimostrarono definitivamente che molte di esse avevano, come orbite, delle curve chiuse, invece che parabole o mere e semplici linee rette; in altre parole, questi corpi avevano cessato per sempre di essere responsabili di superstizioni.

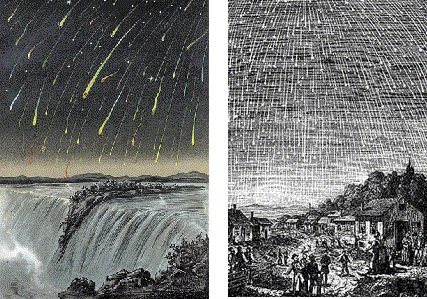

In the 1799 Leonid meteor storm in Latin America: the French explorer Bonpland reported that so many shooting stars were seen that “there was not a region larger than three times the Moon which was not filled at all times with meteors.” On board his ship, at 3 in the morning, Andrew Ellicott was called to witness the phenomenon, and wrote in the ship’s log that “the entire sky appeared as if illuminated by celestial rockets, which disappeared only with the rising of the Sun”. In 1833 the most intense meteor shower associated with the Leonid shower was recorded. A South Carolina planter was awakened by the desperate cries of slaves on his and two other plantations. He heard a voice calling his name and exclaiming “Oh my God, the world is on fire!”. Rushing outside, he didn’t know whether to marvel more at the celestial spectacle or at the multitude of blacks, prostrate face down, imploring God to save themselves and the world. And undoubtedly many thought that the world was about to end (source Uai)

Nel 1799 tempesta meteorica delle Leonidi in America Latina: l’esploratore francese Bonpland riferì che si vedevano così tante stelle cadenti che “non c’era una regione più grande di tre volte la Luna che non fosse piena in ogni istante di meteore”. A bordo della sua nave, alle 3 del mattino, Andrew Ellicott venne chiamato ad assistere al fenomeno, e lasciò scritto nel giornale di bordo che “l’intero cielo appariva come illuminato da razzi celesti, che scomparvero solo con il sorgere del Sole”. Nel 1833 viene registrata la più intensa pioggia meteorica associata allo sciame delle Leonidi. Un piantatore della Carolina del Sud fu svegliato dai pianti disperati degli schiavi della sua e di altre due piantagioni. Sentì una voce che lo chiamava per nome e che esclamava “Oh mio Dio, il mondo è in fiamme!”. Precipitandosi all’esterno non sapeva se meravigliarsi più per lo spettacolo celeste o per la moltitudine di neri, prostrati a faccia in giù, che imploravano Dio di salvare loro stessi e il mondo. E indubbiamente molti pensarono che il mondo stesse per finire (fonte Uai)

In 1916, the American astronomer Percival Lowell, director of the observatory in Flagstaff, Arizona, famous for the study of the planets and in particular Mars, died.

Nel 1916 muore l’astronomo americano Percival Lowell, direttore dell’osservatorio di Flagstaff, in Arizona, famoso per lo studio dei pianeti ed in particolare di Marte.

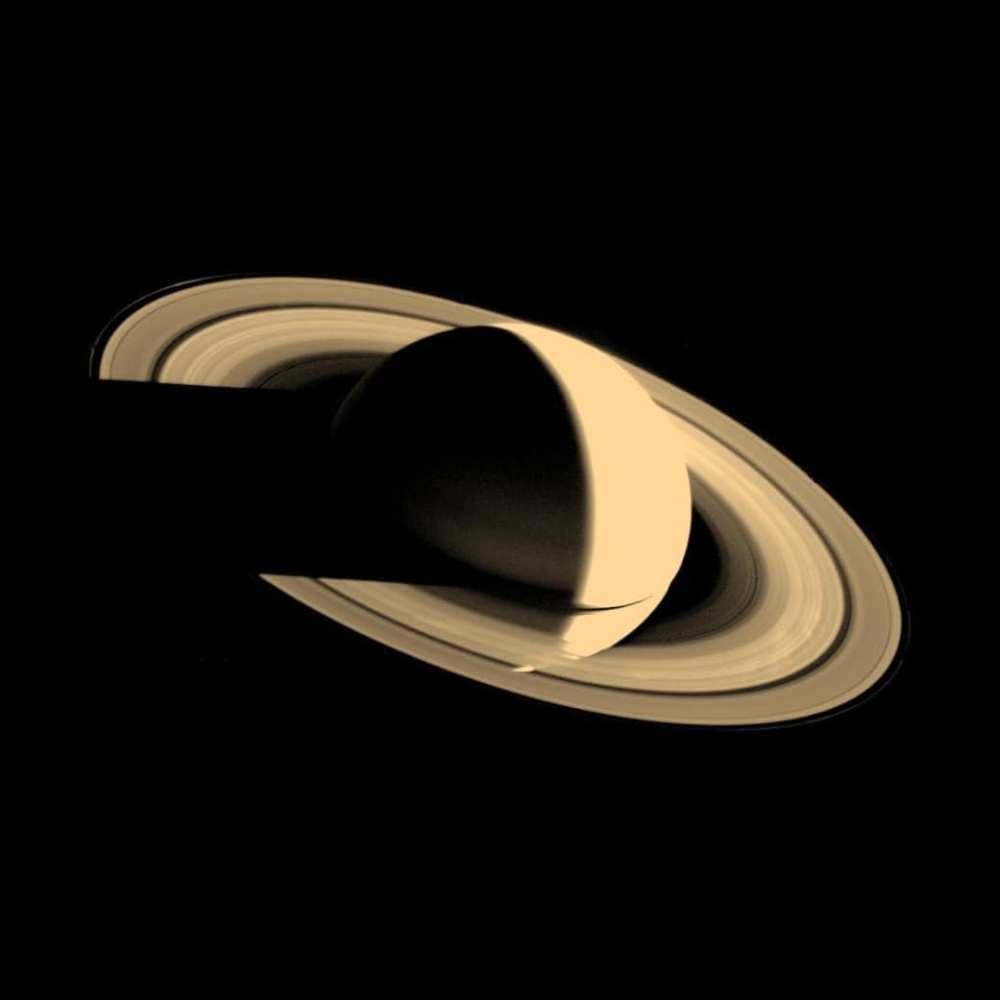

In 1924, the French astronomer and French aeronaut Audouin Dollfus was born, a specialist in studies of the solar system and discoverer of Janus, the tenth moon of Saturn (see photo of the Cassini probe).

Nel 1924 nasce l’astronomo francese e aeronauta francese Audouin Dollfus specialista in studi sul sistema solare e scopritore di Janus, la decima luna di Saturno (vedi foto della sonda Cassini).

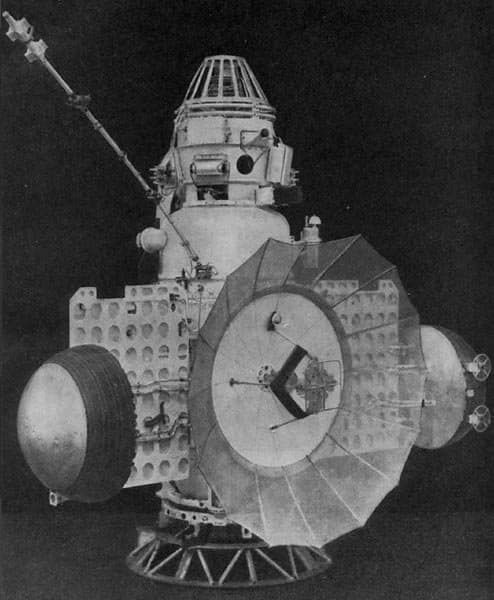

In 1965, launch of the interplanetary probe Venera 2 (see photo)

Nel 1965 lancio della sonda interplanetaria Venera 2 (vedi foto)

In 1980, NASA’s Voyager I probe made its closest pass to Saturn (see photo). See video: https://youtu.be/bVFkVjphIEQ

Nel 1980 la sonda Voyager I della NASA compie il suo passaggio più ravvicinato a Saturno (vedi foto). Vedi video: https://youtu.be/bVFkVjphIEQ

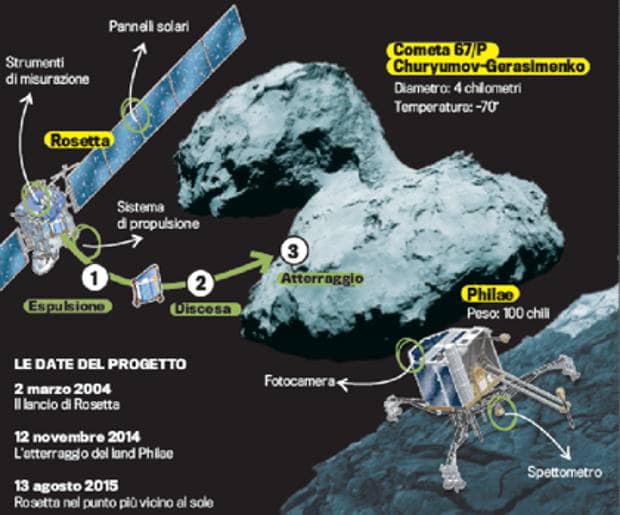

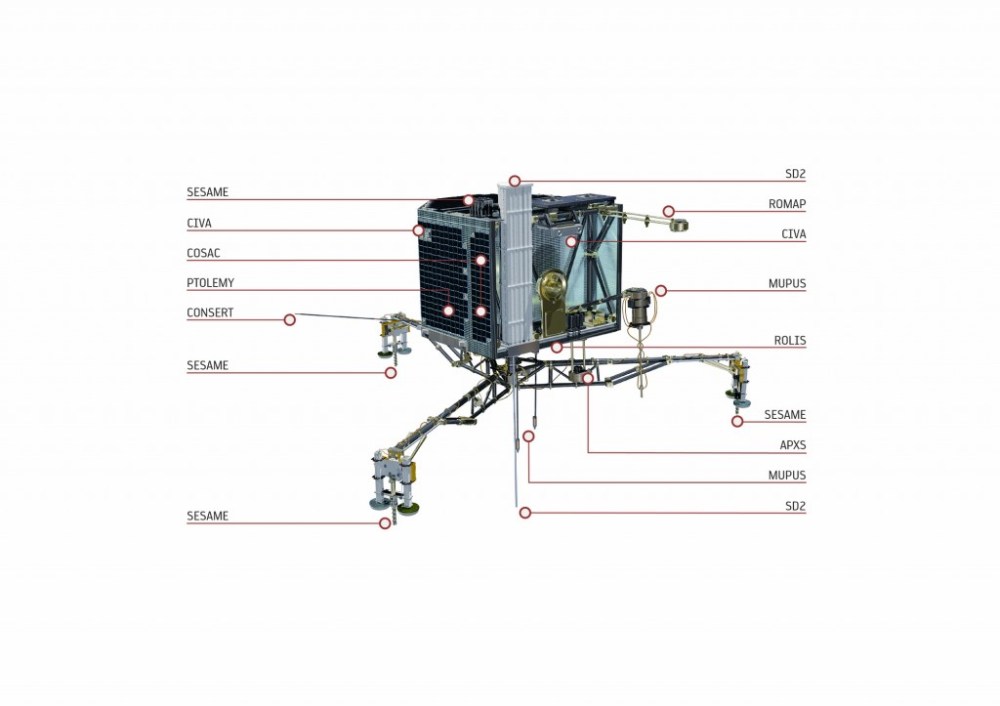

In 2014 the Rosetta probe, 10 years after launch, landed on the surface of comet 67P/Churyumov Gerasimenko (see photo); let’s enjoy this waltz with Rosetta: https://youtu.be/PUpSVxoCcik

Nel 2014 la sonda Rosetta, dopo 10 anni dal lancio atterra sulla superficie della cometa 67P/Churyumov Gerasimenko (vedi foto); gustiamoci questo valzer con Rosetta: https://youtu.be/PUpSVxoCcik

To receive the Astronomy Bulletin Of the Day in your inbox, please put your email address on the contact form: https://abod.blog/contacts/

Per ricevere il bollettino per gli astronaviganti giornaliero nella tua posta elettronica, inserisci la tua mail nel form contatti: https://abod.blog/contacts/

Text, images and video source: Wikipedia, NASA, YouTube, UAI

Sostieni anche tu Wikipedia

Google translate